Harrison Explores Challenges of Female Sportscasters in New Book

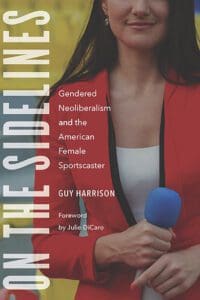

Journalism and Electronic Media Assistant Professor Guy Harrison recently published his first scholarly book, On the Sidelines, which explores the systemic sexism and racism that female sportscasters face in the workplace and that gendered neoliberalism maintains this status quo.

Journalism and Electronic Media Assistant Professor Guy Harrison recently published his first scholarly book, On the Sidelines, which explores the systemic sexism and racism that female sportscasters face in the workplace and that gendered neoliberalism maintains this status quo.

Read the book summary below followed by a Q&A with Harrison about the book’s research process and discussing these topics in the classroom:

When sports fans turn on the television or radio today, they undoubtedly find more women on the air than ever before. Nevertheless, women sportscasters are still subjected to gendered and racialized mistreatment in the workplace and online and are largely confined to anchor and sideline reporter positions in coverage of high-profile men’s sports. In On the Sidelines Guy Harrison weaves in-depth interviews with women sportscasters, focus groups with sports fans, and a collection of media products to argue that gendered neoliberalism—a cluster of exclusionary twenty-first-century feminisms—maintains this status quo.

Spinning a cohesive narrative, Harrison shows how sportscasting’s dependence on gendered neoliberalism broadly places the onus on women for their own success despite systemic sexism and racism. As a result, women in the industry are left to their own devices to navigate double standards, bias in hiring and development for certain on-air positions, harassment, and emotional labor. Through the lens of gendered neoliberalism, On the Sidelines examines each of these challenges and analyzes how they have been reshaped and maintained to construct a narrow portrait of the ideal neoliberal female sportscaster. Consequently, these challenges are taken for granted as “natural,” sustaining women’s marginalization in the sportscasting industry.

What inspired you to take up this research project?

I’ve long been intrigued with how sports and sports media are so definitively gendered. Sports broadcasting especially has always had certain roles for men and certain roles for women, it seemed. As I began my career as a scholar, I immersed myself in the preexisting research examining gender in sports media and what I read typically contradicted with what I was seeing on television.

I’ve long been intrigued with how sports and sports media are so definitively gendered. Sports broadcasting especially has always had certain roles for men and certain roles for women, it seemed. As I began my career as a scholar, I immersed myself in the preexisting research examining gender in sports media and what I read typically contradicted with what I was seeing on television.

The research, which was mostly statistical, showed that the industry was predominantly male, that women in the industry often felt marginalized, and audiences generally viewed women sportscasters as less credible than their male peers. And yet, when I watched ESPN, there seemed to be an equal number of men and women sportscasters on the air and the women seemed to be given an equitable platform to provide insightful analysis and reporting. But then I came to understand ESPN to be a misrepresentation of what gender truly looks like in the sports broadcasting industry.

With this project, I set out to define, through women sportscasters’ experiences and insights, what it truly means to be a woman working in on-air sports media positions. In previous research, we had bits of important information that demonstrated that sexism, misogyny, and even racism were (and still are) at play but I wanted to figure out what all that information meant and define it in a sentence or two.

To that end, I found that gendered neoliberalism – or the expectation that women sportscasters “ignore” or “just deal with” a set of contradictory obstacles with little meaningful support – defines not only the woman sportscaster experience but also the way gender operates in the industry as a whole.

How did you go about conducting this research?

This was a three-step project. The foundation of the research was the ten interviews I conducted with women sportscasters from around the country who were willing to speak on the condition that their identities remain anonymous. These women worked in television, radio, and podcasting, and had varying levels of experience – some worked freelance, some were semi-retired, and others were in their first jobs after college.

The second part of the project was a series of focus groups I conducted with sports fans to get their perspectives on women sportscasters. I wouldn’t say that I used their insights to help me define the woman sportscaster experience. Instead, it was as though the sports fans’ insights helped clarify some of the issues the women discussed, many of which the women themselves were often collectively torn.

The third step was an analysis of media products (photos, tweets, videos, audio clips, articles). These products were essentially brought in as evidence — Exhibits A through Z, if you will – of what the women and sports fans were talking about. So, if a group of the women were concerned about the way some sportscasters are expected to dress these days, some of the photos I gathered might provide visual evidence of the current trend in clothing, while I might have also collected news articles that report why women are dressing this way on television.

“Who” is this book for?

I like to say that, if you think On the Sidelines isn’t for you, it probably is.

Most women who work in sports, media, or really the U.S. as a whole have lived the phenomena explored in the book and are quite familiar with it, even if they’ve never heard the phrase gendered neoliberalism. Yes, this is a book about women sportscasters, but it is also, by proxy, a book about being a woman in the U.S. and other advanced capitalist nations (the U.K., Canada, etc.).

All of that is to say: if you really want to know what life is like for a large number of women – and I think most people who aren’t women should strive to do so – On the Sidelines is the petri dish and microscope that allows you to see it in explicit detail, guilt-free.

Although we know there are some very toxic, predatory men in the sports media industry, I argue in the book that much of what we think we know about women sportscasters has been largely written over time by industry practices, not by a single toxic man, or a single group of toxic men. Even some of the women I interviewed admitted to buying into many of the misconceptions many of us believe about gender in sports media.

What is the one thing you would like readers to take away from this book?

I think a major thing is being more thoughtful about the way we support women sportscasters who persevere through the challenges explored in the book, such as harassment and double standards. While I think it’s important to support women who come forward to tell stories of mistreatment or those who “clapback” at their misogynistic critics, we cannot only respond with “thank you” or “sorry you went through that,” or “that guy is trash.”

We need to hold organizations and the industry as a whole accountable for the way women in sports media are treated instead of requiring women to carry the burden on their own. When we focus on perseverance or the men who engage in inappropriate behavior, we not only give the industry a pass but we also confirm that such behavior is the norm for women in the industry and any woman not up to the challenge was not cut out for this business in the first place.

This is especially true for women of color in the industry who, as we know as a result of the recent Rachel Nichols controversy, face the double whammy of sexism and racism (sometimes from other women). Even that controversy showed that we need to focus less on bad individuals and more on the organizations and industries that foster that sort of behavior. It begins with how we (sports media consumers, organizations, and the industry) talk about the mistreatment of women in sports media.

You are now in your second year as part of the JEM faculty. How do you address topics like this with students who are interested in working in sports journalism?

I like to think I address them thoughtfully. I first acknowledge that I’m trying to thread a needle between what I would like the industry to be and what the industry actually is. I would like the industry to treat my students as equals, regardless of their gender, but I know (and openly admit) that this probably won’t be the case. I then show my students how the industry lacks gender equity, but I take different approaches to addressing and discussing this information, depending on what it is.

On topics like workplace and online harassment, I don’t want to discourage my students who aren’t men, so I tend to implore the men in my class that not only should they not behave like that but they are responsible for helping discourage such behavior.

When it comes to the industry’s expectations for appearance, I’m less preachy and I let students form their own opinions; I might ask the class something along the lines of whether or not they think it’s “bad” if a woman uses her good looks to get into and advance in the industry? Truthfully, I don’t fully know the answer to that question myself, so I’d rather give the students opportunities to think through issues like that. Since my students are the next generation of journalists, editors, and producers they will most certainly have a hand in how these issues are dealt with going forward.